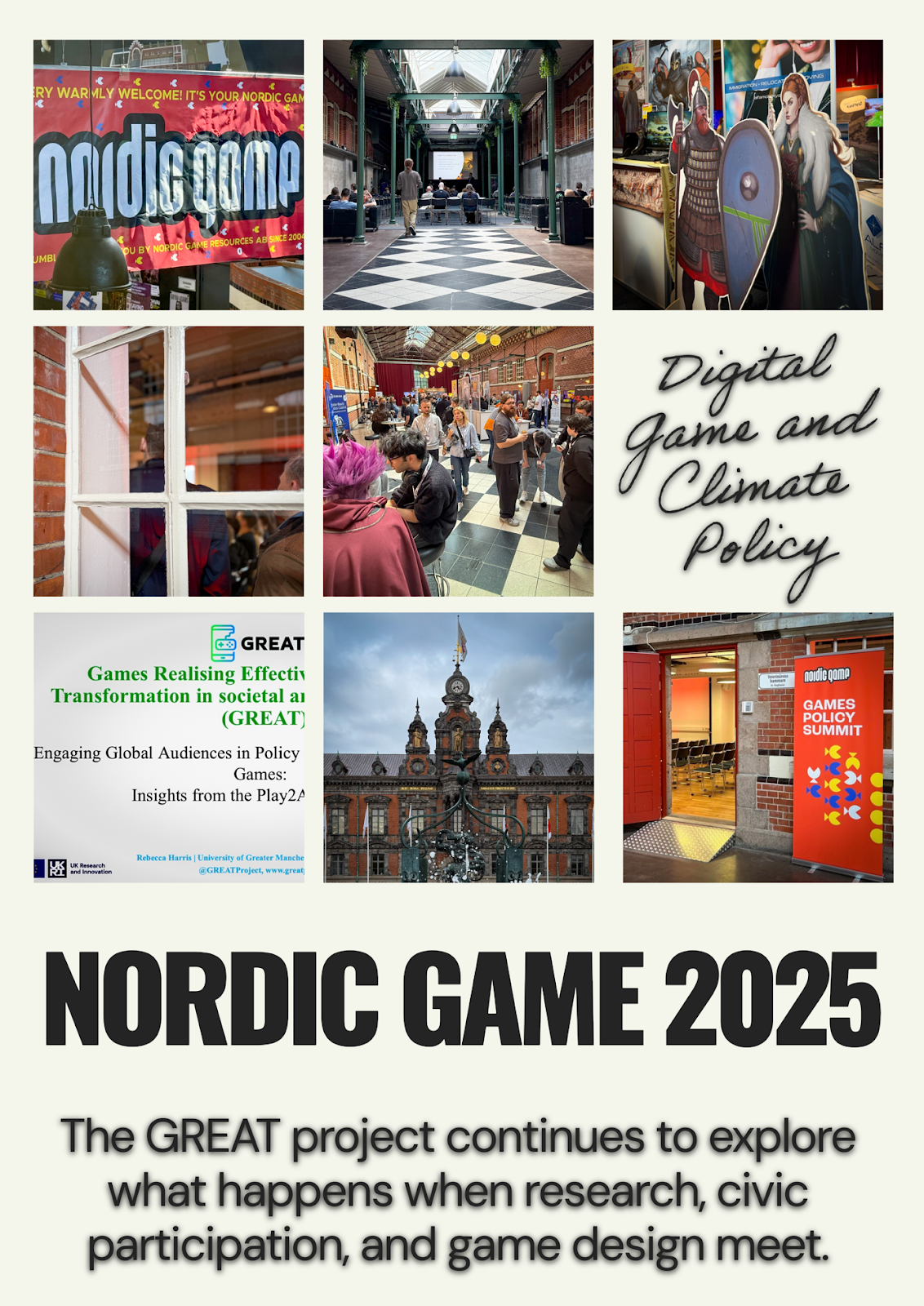

Rethinking Civic Engagement: Reflections from the Nordic Game Policy Summit

At this year’s Nordic Game Policy Summit, the GREAT project took centre stage with a provocative exploration of an increasingly relevant question: What if the next frontier for public dialogue isn’t a public square or a consultation platform — but a game?

Representing the GREAT consortium, Rebecca Harris shared insights from our Play2Act initiative, a bold experiment in embedding policy prompts into digital games. The aim? To reach people who might otherwise be disengaged from formal civic processes — young people, those in politically constrained settings, or simply those fatigued by traditional consultation mechanisms.

Through Play2Act, we engaged over 934,000 players across 228 countries and territories, including many in regions where public participation is limited. In-game, players encountered lightweight, optional opportunities to share their views on climate policy. While these interactions were far from deep deliberation, they served as ambient civic signals — expressions of opinion embedded in everyday digital play.

The core argument of the session was simple but urgent: as digital play spaces increasingly function as de facto civic infrastructures, we need to consider their implications for policy, legitimacy, and governance.

But there’s a critical tension here. As Rebecca cautioned, ‘A click is not always a vote. It’s not always a voice’.

While Play2Act demonstrated how games can invite broad participation, we must be careful not to conflate presence with meaningful engagement. Many players who responded to the climate survey likely didn’t see themselves as engaging in a civic process. The risk is that we over-interpret these signals, mistaking ambient expressions for considered opinions — and in doing so, misread public sentiment.

This insight is central to the next phase of the GREAT project, which is developing a more structured approach to digital engagement through Dilemma-based Learning (DiBL). Instead of simply collecting data, DiBL games invite players into structured reflection and value-driven dialogue. They present real-world dilemmas — like water-saving trade-offs, green jobs, or urban planning challenges — and encourage players to think critically, discuss collectively, and reflect on competing priorities.

Rebecca highlighted three case studies demonstrating this approach in action:

- In the UK, a co-designed game with Waterwise prompted players to weigh up different water-saving behaviours, revealing what people considered reasonable and fair.

- In Vienna, a mobile game engaged over 300 students across nine schools in policy discussions on green jobs, showing how digital spaces can open up policy dialogue to young people.

- In Cyprus, a co-designed serious game facilitated live dilemma sessions with 97 participants, exploring how to green shared rooftops in urban areas and sparking interest from urban planners.

These cases point toward a new paradigm for civic engagement through games — one that is inclusive, reflective, and co-created.

During the discussion, Prof. Dr. Malte Behrmann, the session facilitator, posed a critical question to the audience and panel: ‘What does this mean for game developers who want to break the rules? Why would they want to do this?’

This question strikes at the heart of the evolving civic role of digital play. For developers, ‘breaking the rules’ might mean resisting standard commercial or entertainment-driven expectations to create games that provoke thought, challenge assumptions, and invite meaningful engagement with real-world issues. It means designing not just for profit or entertainment, but for democratic potential.

Why would developers want to do this? Because in an era of climate crisis, rising political polarisation, and digital disengagement, games can offer new pathways for connection, reflection, and action. By ‘breaking the rules’ — designing games that foreground civic dilemmas, transparency, and co-creation — developers can become catalysts for more inclusive and resilient democratic cultures.

Rebecca closed with three design principles that policymakers and designers alike should consider:

- Co-Design Participation: Don’t just design for communities — design with them. Involve youth groups, civil society, and advocates as co-creators, not just testers.

- Transparent Feedback Loops: Close the loop. Show participants how their input is used, share results, and acknowledge contributions to build trust.

- Layered Participation Options: Offer different depths of engagement, from low-barrier actions to more deliberative spaces, to accommodate diverse preferences.

The Nordic Game Policy Summit provided a unique platform for these discussions, bringing together policymakers, designers, and researchers to consider how digital play can contribute to democratic innovation in the face of urgent challenges like climate change.

The takeaway? Games are no longer just recreational spaces. They are emerging as civic infrastructures — sites of expression, dialogue, and engagement.

If we ignore this shift, we risk missing both an opportunity and a warning. But if we embrace it — with care, intention, and accountability — we can open new pathways for policy dialogue that’s not just wider, but wiser.

The GREAT project is proud to be part of this conversation. Stay tuned as we continue to explore how digital play can move from possibility to policy relevance.